The Gubs want our artifacts.

This edited film clip is an example of the historical representation of the Blue Mountains landscape recorded and available on film. Archival film was sourced from the National Film and Sound Archive. The clips have been edited from larger newsreels, short documentaries and home movies.

The selected edited film clip has been produced to demonstrate and dismantle some of the stereotypes created in historical representations of the Blue Mountains landscape as well as to celebrate some of the aesthetic qualities of the recently produced films included in this ebook that make them valuable heritage items for understanding landscape more deeply. Watching the historical archival film, the audience becomes superficial voyeurs of the landscape.

Once considered to be an impassable barrier to the land beyond the convict settlement of Sydney, the Blue Mountains are depicted as an ancient, empty landscape without people. Looking down on the mountains via a white male gaze, the Aboriginal history of the landscape, and the presence of Aboriginal people in the Blue Mountains, had been replaced by a veil of white Australian history making and nation building.

Under the guise of pioneered country, the Blue Mountains landscape is represented as a place of great beauty and wonder, a sublime landscape of economic opportunity, progress and industrialization. In these film clips, there is no reference to Aboriginal people of this country; there is no Indigenous voice on country.

The presence of Aboriginal man Joe Timbery within one edited archival film clip is reflective of, as well as echoing the themes emerging from the recent interviews completed with Indigenous people on Country. The storytellers are pushing against an assumption of absence: that the Blue Mountains are an empty landscape without Indigenous people, and if there are any Indigenous people on Country, they are there to be ‘experienced’ as a people and a culture, for the tourists visiting. Putting on a show for the pleasure of the audience, this clip of Joe Timbery when viewed against the historical context of more recently completed interviews in this ebook is, for me, a patronizing example of the ‘fair dinkum Aussie flavour’ Australia has had to offer for the consumption of international visitors; a ‘real’ Aboriginal person, throwing a ‘real’ returning boomerang ‘a world champion if ever there was one’, continuing a familiar trope within the historiography of Aboriginal history in Australia that Joe Timbery is the true Australian here, part of the landscape, seen and not heard.

I wondered, who was this Aboriginal man Joe Timbery and why is he in the Blue Mountains, dressed in shirt and tie throwing a boomerang for an Olympic Games president? The Timbery family name is well known in Sydney and along the South Coast of New South Wales. I hadn’t expected to come across this name in the Blue Mountains.

I travelled to Huskisson to talk with Jo Timbery’s nephew, 75-year-old Laddie Timbery, and to show him the footage of his Uncle Joe and to see if he could give voice and context to this strange film of Joe.

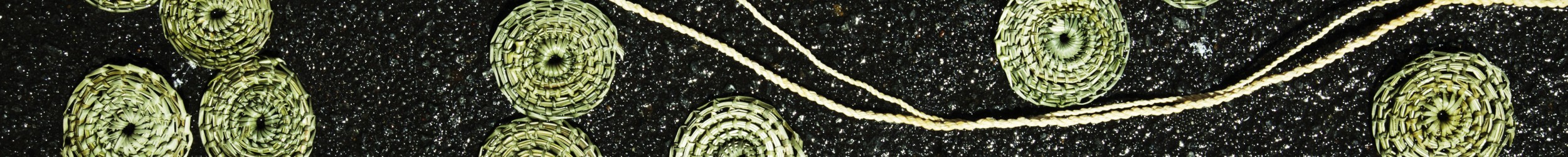

I met Laddie at his Aboriginal Arts and Crafts Workshop at the Lady Denman Maritime Museum at Jervis Bay. He was thrilled to see the film clip of his Uncle and mentioned there were quite a few films like that he has seen. He pointed out the photographs of his family at La Perouse in the 1950s, selling their artworks, and showed me his own artworks and artifacts. Laddie is continuing his family’s tradition to create and exhibit his artworks and to demonstrate to visitors how to throw a boomerang.

I asked Laddie, could he tell me more about his Uncle and why Joe might have been in the Blue Mountains throwing boomerangs for international visitors. Laddie explained his Uncle Joe was invited to travel all around Australia to throw his boomerangs, and often travelled from the South Coast of New South Wales to Dubbo and Wellington (in New South Wales) to find material to make his boomerangs.

Offering to give a demonstration of how to throw the boomerangs Laddie had made himself, he explained his reaction to seeing the film of his Uncle Joe: ‘This was special for us, ‘cause it was all natural boomerangs, mangrove and mulga boomerangs … not plywood boomerangs … we only started making plywood boomerangs forty-nine years ago because the gubs wanted to buy our artifacts and this one is much easier to throw and much cheaper.’[1]

Giving voice and context to the historical film recording of his Uncle Joe, Laddie explained where he grew up, where he was born, where his family was born in Jervis Bay and the landscape of his Country. He is continuing his family’s tradition of engaging in the tourism industry on his own Country at Jervis Bay as an artist and Aboriginal Elder, on his own terms.

Continuing to view the recently made films throughout this ebook, the audience is drawn to an affective dimension of place and landscape: the deep emotion and diverse experience of history telling in place; bearing witness to history making with the body, spirit, and landscape and with Aboriginal voice, the audience becomes much more aware of the historical context surrounding the making and reading of history.

Archival Films

Landscape of the Blue Mountains feature Joe Timbery

Laddie Timbery

Filmed at Lady Denman Maritime Museum, Jervis Bay

Notes

- Laddie Timbery, (27 September 2013), Interview by Julia Torpey, Huskisson.