At the Heart of It … Place Stories Across Darug and Gundungurra Lands is part of my PhD research called ‘History in the Making: Re-imagining heritage, identity and place across Darug and Gundungurra Lands’. The thesis research is linked with a larger research project at the Australian National University called ‘Deepening Histories of Place: Exploring Indigenous Landscapes of National and International Significance’.

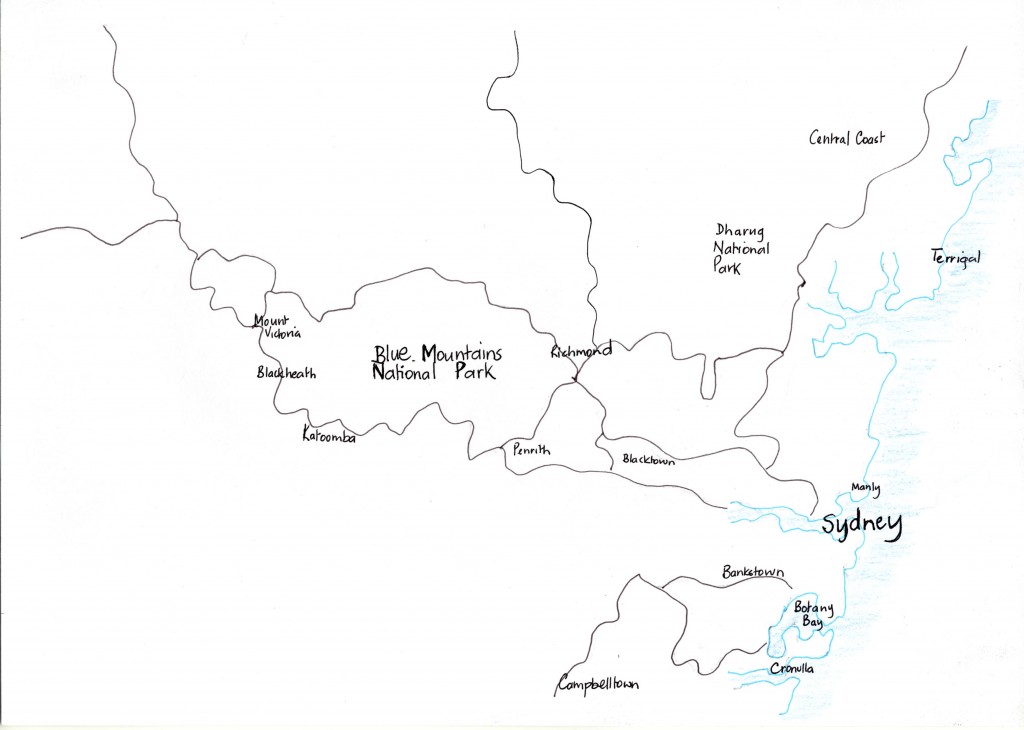

My thesis research has evolved over many hours of filmed interviews between 2011-2013 with Elders, Aboriginal artists, and community members who call Western Sydney and the Blue Mountains ‘home’. Some interviews have been selected here to appear in this ebook from a larger collection of filmed oral histories in place, in the Blue Mountains, Western Sydney and Sydney. This collection of films is not representative of a particular community organization or ‘tribe’; it is representative of individual connection to place and history.

The films in the ebook are illustrative of the diversity of storytelling, history, identity and connection to landscape that I have encountered with individual Indigenous people while being on Country filming, talking and walking with people who are very proud of their Indigenous heritage and ancestry. The result is an ebook that walks and talks and performs history, bringing histories told closer to listeners, readers and viewers.

The idea to create At the Heart of It … developed very slowly. I did not grow up in Western Sydney or the Blue Mountains, so connections, friendships, trust and partnerships had to be established across a wide area. This took time, and a few false starts with many people expressing their doubts about the value of their histories and the value of history in general. These recorded histories have been lived, but many are rarely considered important enough by the storytellers to be told or to be considered as history. ‘Why do you want to talk to me? I don’t think my history is good enough to be on film. Are you sure you want to talk to me?’ was a common question I encountered when I invited people to participate in the project.

I was a new face in the Blue Mountains, Western Sydney and Sydney. My family’s Aboriginal ancestry is from the Sydney area and I grew up in Victoria. Our Aboriginal heritage and history started in Sydney where I continue to develop new relationships with my mother’s birth family, and connection to place. To try to begin to make connections with local Indigenous people in an unfamiliar place, I attended community and organizational meetings, Aboriginal art exhibition openings, culture days and performances in order to become more familiar with my surroundings and the people I hoped to work with. I sent out emails, introduced myself via awkward cold-call telephone conversations and waited at local coffee shops to meet with people and explain this project to them. I asked people to record their histories about their connection to place, and allow me to use those recordings to create my PhD and to create some other products drawn directly from their films. One of these creations is this ebook but on first meeting people, I was still unsure of exactly how their recorded interviews would be made public. Often, my invitation to participate via email and telephone call was met with silence. Slowly however, I began to build individual relationships with people and eventually I was introduced to a local woman who lived in the Blue Mountains, Karen Maber, a proud Darug and Dharawal descendent. I asked her if she would you like to work with me on this project. Karen took some time to consider my offer and hesitantly agreed. She was well aware of the contested nature of Aboriginal histories and often public criticisms they have attracted.

Karen quickly became my eyes and ears of the mountains and Western Sydney, my link with community relaying important information as I travelled back and forth from Canberra to Western Sydney and Sydney and the Blue Mountains with my recording equipment and my phone charger. She was also officially employed as an ‘Indigenous Liaison Officer’ by the Australian National University where the wider Deepening Histories research project was based.

As people slowly began to say yes to our invitations to talk on camera and to visit a significant site of their choosing, as we began to film, interview and experience this process of ‘making history’ on Country, word spread about what we were doing throughout friendship and community groups. We were actively walking, talking and honoring our ancestor’s past, their struggles and our own history and future. I asked the storytellers I was working with, ‘who do you think might like to be involved in this project? Who do you think I need to talk with?’ They would say ‘Oh you need to talk with … they’d be really good in this project.’

The places we visited are individually significant to each person who has shared their history. In this project, ‘Place’ is not just a significant Aboriginal site we might usually refer to if we think of Aboriginal history, landscape and storytelling. In this project, we wanted to cross these boundaries of representation. The contemporary urban landscape of Darug and Gundungurra lands have in the past, made invisible an on-going connection between place, culture and Aboriginal peoples’ belonging. Anthropologist Gillian Cowlishaw has commented: ‘how strange it is that the wealth of imagery, emotional debate and constant reference to the domain of Indigeneity includes virtually no depictions of urban or suburban Aborigines’.[1]

Between 2011 and 2013, I asked to travel to these places with the storytellers, to talk and spend time. I asked could we talk about history, identity, or arts practice? Was it okay to film these histories? Was it okay to film this place? Was it okay to edit these stories we filmed, and create a walking, talking example of how a small collection of Aboriginal people in Western Sydney and the Blue Mountains are thinking about and telling their own history and connection to place? Was it okay to depict the storyteller’s identity and history and connection to Country on camera? The answer was yes.

With little intervention and construction and using film and sound to produce stories told by the storytellers in place, the result is that, together, we are collaborating to produce individual historical records of feelings for place and identity across landscapes of suburban and urban Sydney. We are narrowing the gap between formally acknowledged history producers and history creators.

We did not work with a script or a set of interview questions. As the project progressed, the structure of the narrative had to be found. As relationships were built between the storytellers and interviewer, conversation began to flow more freely. I chose not to direct the storytellers how to tell their history, each person made an informed decision about what they wanted to talk about, and where they wanted to locate their history. We were all treading between the historical, political, social, and cultural boundaries of Aboriginal Australia, Aboriginal History and Australian History. On and off camera the storytellers continued to negotiate a complex contemporary identity that was at once reaching far back honoring their Aboriginal past, whilst at the same time looking forward, creating space for further future dialogue. Telling history in this way has offered an alternative biography of landscape in Western Sydney and the Blue Mountains from what we have viewed on film in the past. There is Indigenous emotion on film, voice, artwork, performance and history and connection to place on film.

Many of the stories told in At the Heart of It … include themes of belonging, and home, finding identity, memories of the landscape as a young person, spirituality, family and Indigenous heritage. Many families in the past had hidden or ‘forgotten’ their Aboriginal ancestry. Others were led to believe their heritage was nothing to be proud of. As we began talking on film, storytellers remembered being with family and community, talking about how people were raised, about where their family was from and how they were perceived by other people in their neighborhood, or by other non-Indigenous family members. When thinking about her family, Darug woman Karen Smith suggests it is not strange at all to think there is a lack of depictions of urban and suburban Aboriginal people. She explains when thinking of her Aboriginal family:

‘There is a lot of pain, there’s a lot of happiness and joy, but it’s extremely emotional. I know that they struggled, and even my grandmother, was … living on the edge … a place where you were living away from the general population.’[2]

Nikki Parsons-Gardiner continues: ‘because we were hit first in this area, well in Sydney and then out in the Hawkesbury and Parramatta area, and a lot of people moved out, or a lot of people were moved in, and because we were the first to have the white bloodlines run through here and people were white skinned, and there was a lot of stigma in the early days, you know, when culture and all that was taken that being Aboriginal was wrong.’[3]

The storytellers in this project are constantly negotiating their identity as Aboriginal people in urban and suburban Australia against an ingrained assumption that to be an Aboriginal person, and to have an Aboriginal history worth sharing, you have to have dark skin, a Dreamtime story and live in Northern Australia. This is a false history, there is more to Aboriginal history in Australia that that.

Notes

- Gillian Cowlishaw, (2009) The City’s Outback, UNSW Press, New South Wales, p 5.

- Karen Smith, (14 August 2012) Interview by Julia Torpey, Manly Dam.

- Nikki Parsons-Gardiner, (11 September 2012) Interview by Julia Torpey, Nurragingy Reserve.